We have heard a lot about OA or Open Access (of journal articles) in the last five years, often in association with the APC (Article Processing Charge) model of funding such OA availability. Rather less discussed is how the model of the peer review of these articles might also evolve into an Open environment. Here I muse about two experiences I had recently.

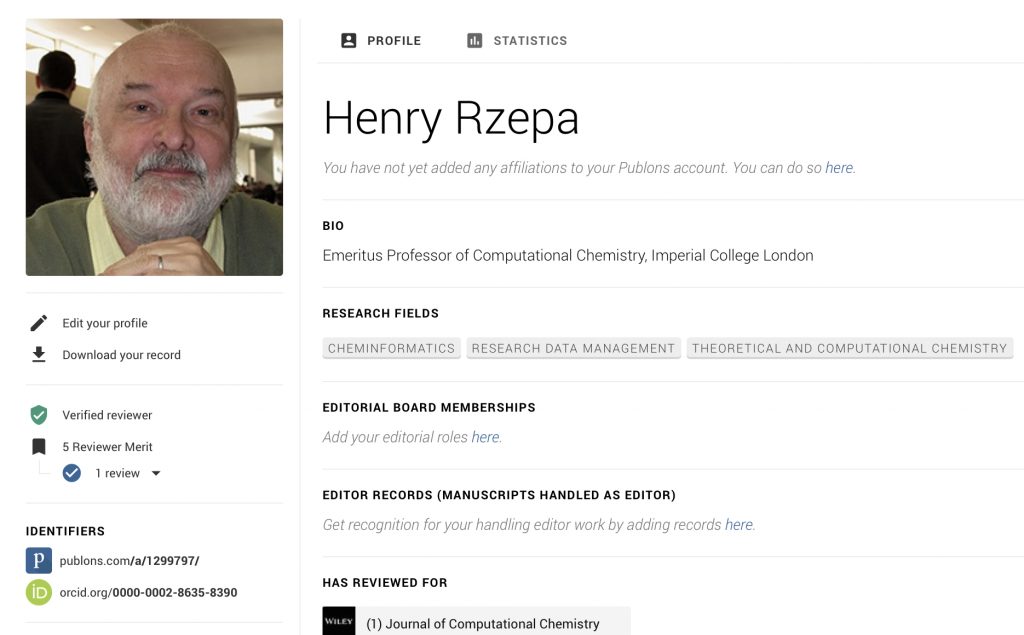

Organising the peer review of journal articles is often now seen as the single most important activity a journal publisher can undertake on behalf of the scientific community; the very reputation of the journal depends on this process being conducted responsibly, thoroughly and with integrity by the selected reviewers. Reviewers undertake this process voluntarily, mostly anonymously, without remuneration or recognition and often with short deadlines for completion. After one such review, I recently received an interesting follow-up email from the journal, suggesting I register my activity with Publons.com, a site set up to register and give non-anonymous credit for reviewing activities. I should say that Publons is a commercial company, set up in 2012 to to “address the static state of peer-reviewing practices in scholarly communication, with a view to encourage collaboration and speed up scientific development”. Worthy aims, but like many a .com company nowadays, one might ask what the back-story might be. Thus many of the Internet giants, Google, Facebook, Twitter etc, do have back-stories, which often underpin their business models, but which may only emerge years after their founding. With only a hazy idea of what Publons’ back-story might be, I went ahead and registered my reviewing activity.

After doing so, I then accessed my entry. You only learn that I have reviewed for a particular journal, but nothing about the actual process itself. I did not really think that this experiment had done much to encourage collaboration and speed up scientific development. It might be useful for early career researchers to get their name exposed however.

I can almost understand why the review itself might not be publicly displayed, but as a result you learn nothing about the factual basis of the review and whether it might have been conducted responsibly, thoroughly and with integrity. Instead, I now suspect that the presence of my name on this site might merely encourage other publishers to deluge me with requests for further (freely donated) refereeing.

Discussing this at lunch, a colleague (thanks Ed!) reminded me of a veritable journal called Organic Syntheses. Here, authors submit a synthetic procedure and open identified “checkers” are invited to repeat the procedure and comment on it. The two roles are kept separate (i.e. the checkers do not become co-authors), but they could get credit for their activity. Thus if you view a typical recent entry[1] you will see a full biography and affiliation of the checkers given at the end, with footnotes often describing their own observations if they differ from those of the authors.

This set me thinking whether an open peer review process might also contain such an element of checking, as well as informed comment, nay opinion, about the article itself and the conclusions it makes. The opportunity arose when I was contacted by an author who was about to submit a computational article to a journal. This journal allowed open peer review. If I agreed to review, my name would be attached to the article if accepted for publication. I undertook this on the basis that I would use this review to conduct some limited checking of the computations and other assumptions underpinning the conclusions in the submitted article. I also wanted this open process to include the data on which my review was based. Most importantly if anyone wished to replicate my replication, the barriers to doing so should be as low as is possible. Shortly thereafter, I received a formal invitation from the journal and I set about my task. Crucially, all my own calculations supporting the review were archived in a data repository, albeit under embargo. In my cover letter I included the DOI for my data and the embargo access code, so that the authors (and the editor of the journal if they so wished) could inspect the data against which I wrote my review.

Then followed standard procedures, whereby the authors took my comments into consideration, revised the article and the final version was indeed accepted and published.[2] You will find the two referees/checkers listed, although unlike Organic Syntheses, there is no bibliographic information about them or their affiliation. I did ask the journal if they could at least link my ORCID identifier to my name, but that request was refused. If my name had been a common one, then disambiguating it into a unique identity could be a challenge. There was also no mechanism to associate my identity on the journal with any data on which I had based my review. Really, the only open aspect of this process was just my (potentially ambiguous) name, nothing else. No follow-up was received from the journal to add the review to Publons.

The next stage was to contact the author who had originally set the process under way to ask them if they would mind my releasing the data on which my review had been based. They agreed, as also they did to my telling this story. The overall outcome is thus a published article with the reviewers (if not their reviews or any supporting evidence for their review) openly named. In this specific case, there is also an open dataset with a formal link back to the article in the form of a DOI (10.14469/hpc/2640, although I suspect this aspect is unique, even precedent setting), but one driven by the reviewer and not the journal. It would be nice to have bidirectional links between both article and the review data, but I do not know any publishers currently operating such a mechanism (if anyone knows such, please tell).

Now to the broader questions about the process described above. I think that the aspiration to encourage collaboration and speed up scientific development may indeed have been promoted by this association between article and the data assembled by the reviewer. Whether the final article was improved as a result of the processes described here I will leave the authors to comment if they wish. As with the checkers employed by Organic Syntheses, such a review process takes not just time, but resources. Resources that currently have to be freely donated by the reviewers and their host institution and which clearly cannot become expensive, time-consuming or onerous. That was not the case as it happens here; my contributions were facilitated by my having sufficient expertise to perform the tasks I undertook really quite quickly.

I will raise one more issue; that of whether to add my review to the dataset which is now openly available. In fact it is not included, in part because it related to the initially submitted version of the MS. The final MS version has been revised and so many of the comments in my review may only make sense if you have the first version to hand. It would be perhaps unreasonable to make the first drafts of manuscripts routinely available (although historians of science would probably love that!) alongside the reviews of that first draft. But I could also see a case for doing so if the community agreed to it. One to discuss for the future I think. There is also the associated issue of what should happen to any dataset associated with a review in the event that the final article is rejected and not accepted. Should the data remain permanently under embargo and the reviewer’s identity permanently anonymous? Perhaps opening up even such datasets might nevertheless encourage collaboration and speed up scientific development, but I fancy some would consider that a step too far!

References

- J. Zhu, "Preparation of N-Trifluoromethylthiosaccharin: A Shelf-Stable Electrophilic Reagent for Trifluoromethylthiolation", Organic Syntheses, vol. 94, pp. 217-233, 2017. https://doi.org/10.15227/orgsyn.094.0217

- L. Li, M. Lei, Y. Xie, H.F. Schaefer, B. Chen, and R. Hoffmann, "Stabilizing a different cyclooctatetraene stereoisomer", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 114, pp. 9803-9808, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1709586114

Tags: Academic publishing, article processing charge, author, Company: Facebook, Company: Publons, Company: Twitter, editor, Electronic publishing, Entertainment/Culture, Hybrid open access journal, Internet giants, OA, Open access, Organic Syntheses, Public sphere, Publishing, Scholarly communication, search engines, Social Media & Networking, Technology/Internet

Here is an interesting commentary entitled To Sign or Not to Sign: A Slice of Transparency in Peer Review in which the merits and demerits of a peer-reviewer making themselves known to authors is discussed.

Hello Henry,

On the issue of usefulness of Publons, I think making the review public, even if the original draft is not available, could help in making reviewers more conscious about how they comment on a paper draft. For the most part, in my experience reviewers are very professional in their comments. But a public review could reduce the number of dismissive or belittling comments that are out of place in an academic review. Not that I have had too many of those, only ocassionally.

Just my $0.02

Victor

Most of us who have received (anonymous) referee comments from a journal have encountered dismissive or belittling comments, although I agree they are not the norm. A colleague once showed me comments that even verged on the abusive (he contacted the journal to in effect complain the editor was not doing their job by transmitting such abuse, and indeed received an apology and a promise that this referee would be removed from their list). Anonymity as propagated by journals has other interesting effects; it’s not entirely unknown to be approached at conferences by authors convinced you reviewed (and rejected) their papers. On the occasions it has happened to me, the authors as it happens were mistaken!

Many journals also now offer authors an option to suggest names of possible referees, and even to try to blacklist other names from being used as referees, all the while trying to preserve the pretence of anonymity. As an author, I tend to refuse such nomination, but occasionally one encounters an article submission system where completion is prevented until such names have been provided. And whilst I am dealing with the iniquities of the whole system, some journals try to develop/enhance their brand by claiming to reject e.g. > 80% of all submissions, most of which are never sent to peer review at all but with the decisions taken by more junior editorial staff.

There is no doubt in my mind at least that the system does need reform and new ideas. OPR is perhaps one such?

Here is an article entitled The Ethics of Scientific Publishing: Black, White, and “Fifty Shades of Gray” (DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.009) in which the quote “the vast majority of (researchers) in medicine believe that more than half of published results are simply not reproducible” appears. The article ends with this statement on the role of data: The “clean” system of the future may well not involve scientific publications in their current form at all. It is unlikely that journals will die when scientific data start being routinely posted on publically accessible websites; they will simply take on a new function, which might be called “journalism.”

Yes indeed, as I have here argued in 2013, journals will tell the story, whilst e.g. data repositories will handle the associated data and peer-reviewers will review both!

This is certainly a hot topic: time-to-open-the-curtains-on-peer-review where review transparency, and the full blown open peer review, is discussed.