I have mentioned the Amsterdam manifesto before on these pages. It is worth repeating the eight simple principles:

- Data should be considered citable products of research.

- Such data should be held in persistent public repositories.

- If a publication is based on data not included with the article, those data should be cited in the publication.

- A data citation in a publication should resemble a bibliographic citation and be located in the publication’s reference list.

- Such a data citation should include a unique persistent identifier (a DataCite DOI recommended, or other persistent identifiers already in use within the community).

- The identifier should resolve to a page that either provides direct access to the data or information concerning its accessibility. Ideally, that landing page should be machine-actionable to promote interoperability of the data.

- If the data are available in different versions, the identifier should provide a method to access the previous or related versions.

- Data citation should facilitate attribution of credit to all contributors

I just gave a talk at the ACS meeting in Dallas which touched upon the need to emancipate data according to these principles. My talk, in case you are interested, focused particularly upon item 6 above.[1]

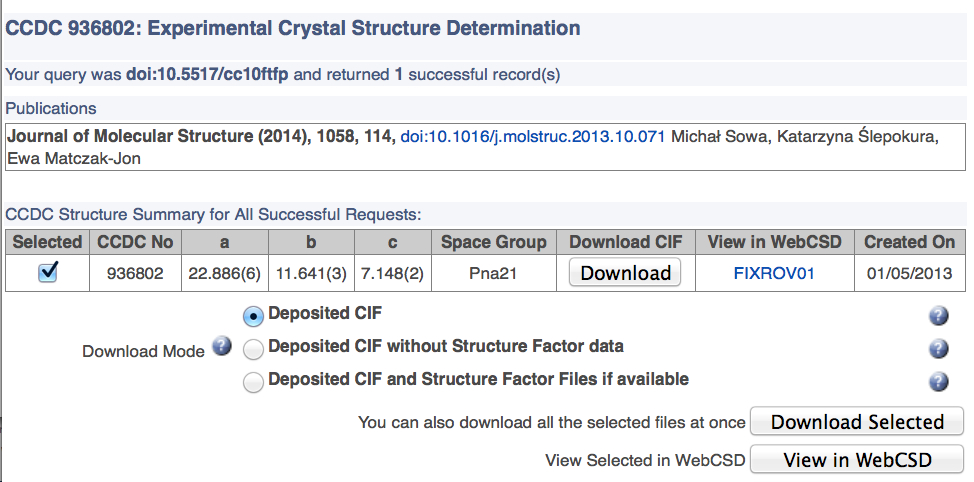

Just after my talk I heard that crystallographic data was about to be emancipated (my phrase) and so I was interested to find out what this might mean, and how many of the above principles were being adhered to. Indeed, it is an interesting test to apply to any chemistry data that you might find out there. Thus 10.5517/cc10ftfp[2] is the DOI of a recently published crystal data structure. This adheres to points 1-3 and 5 above, and probably also 8. As I have already noted, 6 is the interesting one! So let’s go to the landing page and see what we find.

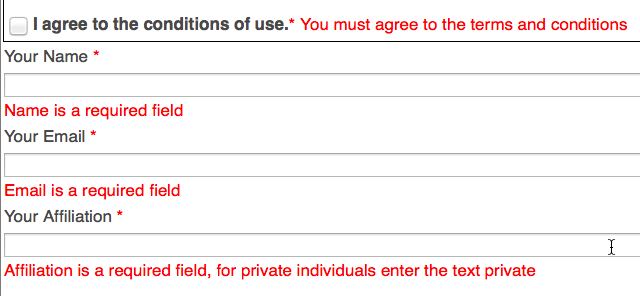

Firstly, note that you do not need any sort of access code to get to this page, it is open to all. But it is after all just a landing page, not actual data. Next, click on the Download button, and you get asked to identify yourself by providing a name, email address and affiliation as mandatory fields, as well as agreeing to conditions of use. I reproduce these conditions here:

“Individual CIF data sets are provided freely by the CCDC on the understanding that they are used for bona fide research purposes only. They may contain copyright material of the CCDC or of third parties, and may not be copied or further disseminated in any form, whether machine-readable or not, except for the purpose of generating routine backup copies on your local computer system“.

As with most such conditions, it is what one cannot do that is most interesting.

- Teach, as for example incorporating the data into lecture notes

- Make a copy, e.g. to place into this blog (is this for research purposes?)

- Do bona fide research purposes in fact allow a copy to be made, or does the second sentence over-ride the first in this regard, since it lists exclusions and research copying is not an exclusion.

- Judging from the landing page, it is pretty much impossible for any machine action to take place (item 6 in the Amsterdam manifesto). Even though the data is machine actionable, the landing page pretty much prevents this from happening.

What did cause my eyebrows to shoot up was that I have to reveal my full identity and affiliation (which appears not to be actually checked) in order to get the data. Think about this. Do journals ask for this information when you download an article from them? (OK, they probably know your affiliation). Which scientist is reading which article (or viewing which data) could be construed as sensitive information after all. So why in order to acquire crystal data do you have to provide personal information? Surely, looking at data should be a private process if one wants it to be?

The release of crystal data in this manner, with a decent partial adherence to the Amsterdam Manifesto is an excellent start; this data after all is well curated and of high value. But I must call upon CCDC to rethink that landing page, the conditions of use and the mandatory gathering of personal information. Not quite there yet!

References

- Sowa, Michał., Ślepokura, Katarzyna., and Matczak-Jon, Ewa., "CCDC 936802: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination", 2014. https://doi.org/10.5517/cc10ftfp

Tags: ACS, Amsterdam, Amsterdam Manifesto, Dallas, scientist

I’d just like to opine here that citability implies permanence: that to cite something, you have to be reasonably sure that it won’t be updated or changed without changing the reference. This is not to say that data *shouldn’t* be updated with errata or new information, but that the reference for that updated form should change such that a citation made on the basis of an un-updated form is still clear and accurate.

Many people have begun to conflate having a DOI with being citable, in response to which I’d direct them to this article:

“DOI != citable”, by Carl Boettiger.

I’d also say that to aid this, if your data can be accessed in multiple forms, it’s probably best to nominate one as a canonical form from which all others are presumed to be derived, in case of accidental (or intentional!) conflicts.

I assume the CCDC use that personal information to justify obtaining further funding for their maintenance of the service — I personally think that in those cases it can do a lot towards getting good results to state that explicitly, so that it doesn’t look like pointless privacy invasion.

Re: conflation of a DOI with being citable. To my mind, a DOI means that there is decent metadata associated with the object. Sufficient to make the data valuable in some sense. That also makes it worth citing.

Re personal information capture. The capture of such information to satisfy sponsors/funders is very much the thin end of a scientific wedge. I personally think that such encroaching invasion of privacy should be resisted.